(This is a sequel to the preceding post, “Menippus and the Stranger”. Philostratus doesn’t continue the story this far in his Life of Apollonius, but I felt as if poor Menippus was entitled to an ending that offered at least a little hope. After all, in the original story, Menippus survived. That said, what emerged from my brain wasn’t exactly a more hopeful ending. Sometimes, a story goes in the direction it wants to go.)

The sharp pain of being devoured by Empedia abruptly stopped—but not the sharper emotional pain of being rejected by her. Menippus found himself staring up at the night sky. A fog must have rolled in, though. The moon was a large, bright blur. The stars were barely perceptible sparkles.

He felt cold, but he didn’t shiver. No, not cold exactly. He was more numb than cold.

Despite the dim light, he suddenly became aware of two figures above him. Though they both looked as if they had been carved from shadow, they were much more distinct that anything else he saw, and they looked different from each other.

To his right stood a cowled, faceless figure who reached out to Menippus with more or less human-looking hands. To his left stood a figure whose bright white fangs were visible against a dark face. It also reached toward him, but its hands were more like claws.

The two figures became aware of each other at the same instant.

“Brother,” said the fanged one in a voice that resonated like a battle cry. “This one is mine, for his death was violent. It is unlike you to violate the rules in this way.”

“Sister,” replied the other apparition in a voice like bone grinding against bone. “His death should not have been violent. In fact, he should not have died this night. Something is seriously wrong.” Though his words were ominous, his tone was flat and emotionless.

“Perhaps, but it is not our job to determine what is wrong. I come to drink his blood, not to investigate his death.”

“As far as his blood is concerned, you may have it—if you can get any of it away from Empusa.”

Menippus heard slurping and chewing somewhere below him. He tried to ignore them and clutched his numbness around him like a cloak.

The white-fanged apparition looked right through Menippus and shrieked in disgust. “It is too late. There is no blood left.” Without another word, she unfurled her dark wings, which Menippus had mistaken for a cloak, and flew away.

Her brother again reached out his hand to Menippus. “Take my hand, and come away from this place with me.”

Menippus’s sluggish mind finally figured out who the dark figure was. “Thanatos, I cannot go with you. I must remain here.”

“To what end?” he asked, still reaching for Menippus. His hand looked much closer, though his body didn’t seem to have moved.

“Now that I am out of my physical body, maybe Empedia and I can find our way to a spiritual relationship.”

For perhaps the first time in human history, Death was momentarily stunned into silence.

“You…Uh, Empusa is not capable of such a relationship,” he managed after a long pause. “She has departed without the slightest backward glance, even though she could see you floating there as well as I can. Take my hand!”

Menippus tried to turn and see if Empedia—Empusa, he supposed, was her real name—was truly gone. But Thanatos stopped Menippus by grabbing the young scholar’s head with both of his chilling hands.

“There. You cannot stop me by refusing to take my hand. You have felt my touch, which makes your death official. Hermes will be along soon to collect you.”

“Indeed, I am here already,” said Hermes, who flew up to us so fast that I saw him only as a blur until he stopped moving.

It was strange indeed to see so many beings whose existence had been questioned by philosophers for centuries. But the handsome youth, with his sparkling white chiton, winged sandals, winged helmet, and most of all, his caduceus, glowing with magic, looked exactly as the tales said he should. What would Plato, with his insistence on the idea of one god, perfect and eternal, have said about the messenger god? Or about cold, gloomy Thanatos and his bloodthirsty sister, Ker, for that matter?

Or about Empusa? Menippus knew she was real. If he could manage to break Death’s grip and turn his face toward the ground, his corpse—what was left of it, anyway—would bear witness to just how real she was.

“This one must still have a spell upon him, left over from his life, that compels him to love Empusa,” said Thanatos.

Hermes looked at Death and raised an eyebrow. “Such spells always end when the victim’s life does. Always.”

“See for yourself,” replied Thanatos. “I have performed my function.”

He unfurled his own midnight-black wings and soared into the sky. Hermes squinted at Menippus, made the caduceus glow, and held it up to the young philosopher’s face.

“Magic does cling to you,” he said, his eyes widening. “But I should be able to remove it.”

“Please don’t!” cried Menippus, grabbing Hermes’s wrist. If the old tales spoke true, such an act might have brought upon him the god’s wrath, but either such tales were false, or Hermes was in a good mood. Either way, he gently brushed aside Menippus’s hands.

“Why would you want the burden of such an unnatural love upon you? It will do you no good. Whatever romantic notions you may have about seeking out Empusa in the Underworld are but a dream that can never be fulfilled. Unlike we younger gods, she is an elder being who does not have thoughts and feelings similar to those of mortals. The only attraction she ever had to you was to your mortal flesh and blood—which you no longer have.”

“There must be some way we can be together,” replied Menippus. “Please help me!”

“The only help I can give you is to remove the magic that binds you to her. That should not have remained attached after your death, anyway.”

Menippus started to protest, but the caduceus suddenly blazed with power, nearly blinding him and making him tingle all over. Both the blindness and the tingling faded quickly.

“I…I still feel the same,” said Menippus, realizing immediately after that he should have stayed silent. But it was too late now.

Hermes examined him again by the light of the caduceus. “You speak the truth—yet that cannot be the truth unless—could it be?” He stared at Menippus so intensely the young philosopher feared that the god would stare him right out of existence. After all, the body that Menippus seemed to have now was merely an apparition. How much divine scrutiny could it endure?"

“You have magic of your own,” said Hermes. “That is almost unheard of…unless you are a descendant of gods.”

“I’ve never worked magic,” said Menippus. His teacher, Demetrius, would have laughed at such an idea.

“Ah, but you have,” said Hermes. “You just never realized it. Your magic responded to Empusa’s magic, but instead of trying to repel it, your magic reinforced hers. That is why you chose to ignore the wise counsel of Apollonius. I can still remove the spell, but breaking it against your will may injure you.”

Menippus fell to his knees—or at least tried as well as he could, from his position floating in midair. “Great Hermes, I beg you not to do that. I will learn to bear the pain of unrequited love.”

In fact, Menippus was certain he would suffer more from its absence than its presence.

Hermes sighed loudly but didn’t immediately respond. That gave Menippus an opening to ask another question.

“From what god am I descended?” It would have been an arrogant question if Hermes hadn’t already confirmed Menippus’s divine descent.

The messenger of the gods hesitated a moment before replying. “That doesn’t matter. The divine-mortal coupling happened so long ago that your divine ancestor will feel no particular need to intervene on your behalf. In truth, such interventions have declined steadily since the Trojan War, well over a thousand years ago.

“It is time to go now,” Hermes continued before Menippus could interrupt again. “As a psychopomp, it is my duty to see that you reach the Underworld as quickly as possible.” Hermes turned and started to fly away. Menippus found himself ensnared by Hermes’s magic and swept along behind him.

They flew high and fast. Menippus expected to be tossed about by combination of speed and wind, but he felt nothing. How many times would he be reminded that he was dead and incapable of such physical sensations?

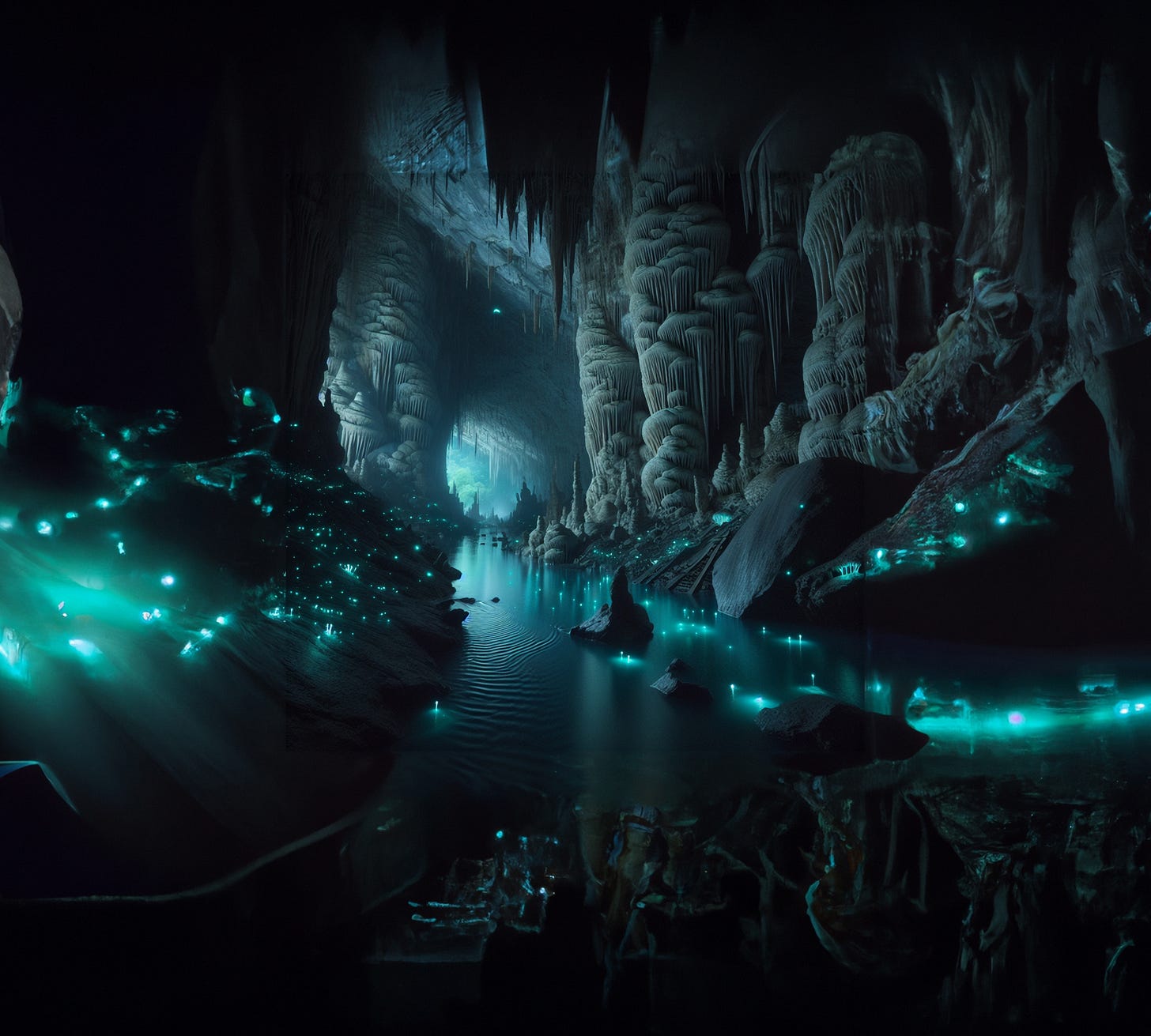

Hermes began to descend as they approached Cape Tanaeron, the southernmost point on the Greek mainland. Menippus got a quick glimpse of the gray and light brown stones that formed the upper part of the cave-like Oracle of the Dead. before they glided down the hillside. In a second, they reached an actual cave and sped through it until they arrived in a massive, gloomy cavern.

There was no obvious light source, but Menippus could see, anyway. Hermes had landed him on a rocky beach. He could hear the distant rush of a river—Acheron, no doubt—but he could not yet see it. Hordes of people blocked his view, some moving purposefully toward the sound of water, others wandering aimlessly, at least as far as he could tell.

“This is as far as I normally go,” said Hermes. “Work your way through the crowd, find Charon, and give him your obol for passage across the river.”

“I…I don’t have any coin,” replied Menippus, looking around as if he expected one to magically appear.

“Someone will need to give you proper burial rights and supply the coin,” said Hermes. He closed his eyes for a moment, then opened them and smiled a little. “Apollonius is leading Demetrius to where you died. They will take care of you shortly.”

“Should I just stand here?’ Menippus asked. But Hermes was already gone. He had vanished so fast that the young philosopher took a second to notice.

Menippus had nothing to do but look around, hoping to catch a glimpse of Empusa. But why would she come here, where there was neither flesh nor blood?

Trying to put his quest for Empusa out of his mind, Menippus pondered what Hermes had told him. The young philosopher had divine blood in his veins, though apparently, not a lot. But he also had magic—perhaps more than a little. Whatever divine power Apollonius had been gifted had cracked all of Empusa’s illusions with ease. But the love spell that now bound Menippus by his own choice remained intact.

Magic was supposed to be able to perform amazing feats. Was it not said that Thessalian witches used to be able to pull the moon down from the sky? The Menippus who had existed just a few days ago would have laughed at such a question. But the current Menippus, trapped in a gloomy cavern with a large mass of people who seemed largely unaware of him and each other? He might be willing to entertain almost any speculation, test any theory, however wild.

Hermes hadn’t told him who his divine ancestor was. That probably meant the guide of the dead thought that knowledge would pull Menippus in the direction opposite from the way the god wanted him to go. Did that mean his ancestor was powerful? Probably. But knowing that didn’t do Menippus much good. He needed to know who that mystery ancestor was.

But was there anyone he could ask? None of the ghosts shuffling around near him would know any more about it than he did. He could shove his way toward Charon, but if the old tales were true, he doubted that Charon would have the slightest interest in talking to him.

He tried to return to the mortal realm by the same passage through which he had entered, but he found no visible tunnel leading back outside—no doubt, a safety precaution to keep the dead from escaping back into the world of the living.

That discovery led to wandering aimlessly as he had seen some of the other ghosts do.

Or were his movement truly aimless? He found himself on the river bank, staring at the Acheron as it roared past. The myths were clear that only passengers in Charon’s ferry could get across. But they were not clear what would happen if someone tried to cross the river without Charon. Perhaps nobody had ever been stupid enough to try.

Though Menippus knew he no longer possessed a physical body, he could look at himself and at the others and see what looked like bodies. If he thought about it, he could also feel the rocky beach beneath his feet. A river shouldn’t have been a barrier to him or any of the other phantoms. But if that were the case, Charon would get bypassed all the time. That must mean the rules in the Underworld were different than they were in the realm of the living. The river must hold some danger for the souls who tried to cross it.

Visions of horrible monsters lurking beneath the surface sprang into his mind. Or perhaps the river would just sweep him away, and he would be lost forever. But he was dead, after all. Dead and cut off from Empusa. How much worse could his situation possibly get?

However, there was one other step he could take before “taking the plunge.” Perhaps Underworld rivers, like their aboveground equivalents, had gods within them. Given all the other strangeness he had witnessed, it was certainly worth a shot.

“Mighty Acheron, hear me. I come to you as a humble suppliant, seeking help only you can give.”

His voice echoed quietly in the cavern, but he heard no response. Nonetheless, he continued talking. If there was a river god hidden in the rushing water, he probably wasn’t used to receiving prayers. Besides, what else did Menippus have to do?

After what seemed an unbearably long time, Menippus heard a voice gurgling in the water. At least, he thought he did.

“Who disturbs my rest?”

That wasn’t the most promising beginning, but Menippus had little to lose by persisting.

“I am Menippus, a forlorn lover seeking your aid.”

A sound that might have been a chuckle gurgled up from the river.

“What do I care about you or your love?” The voice sounded bitter. Perhaps that gave Menippus an opportunity.

“The gods have ill-treated me, their descendant. You have a grievance against the gods yourself, do you not?” He knew such a line of conversation was risky at best. If he ever got to the three judges who would decide his afterlife, would this conversation count as blasphemy and doom him?

“My grievances are none of your business,” replied Acheron. The racing water thrashed for a moment like a giant serpent. But then, much to Menippus’s surprise, the river god continued.

“I am not like other river gods, for I was not born of Oceanus and Tethys. Instead, my mother was Gaia, the earth herself, and my father was Helios, the glorious sun, whose beams sparkled in my every drop.

“I should have had a bright future, but instead, I was banished down here, into the darkness—and all for the supposed crime of letting the titans quench their thirst with my water during their war with Zeus. I have been here ever since, with no hope of parole or pardon.”

“Then, since I, like you, have been wronged by the gods, let me pass.”

For a moment, the river stopped moving completely, as if Acheron couldn’t believe his ears. “What could the gods possibly have done to you that would give you a grievance equal to mine?”

Menippus told him every details that he could remember. He poured out all his pain—and in exchange, he got only insults.

“This is nonsense. If anything, the gods tried to spare you, and you destroyed yourself through your own stupidity. You are not the brother in suffering that you claim to be.”

“Nonetheless, I do suffer,” Menippus replied. “The gods may not have afflicted me as much as you, but helping me would annoy them, would it not?

“It might,” admitted Acheron. “But what aid could I possibly give you? I cannot change my course nor my water level. And if you try to swim across, the sorrow and pain that burns in every drop of my water will overcome you.”

“There must be something you can do,” said Menippus. “At least, let me try to swim across . If I fail, you have lost nothing. If I succeed, my divine ancestor may be able to help you.”

The last suggestion was greeted by another watery chuckle. “I doubt that. I feel your connection to a god, but you are many generations removed from him. However, if you know him, name him.”

Menippus could do nothing but guess. “Eros,” he said. It made sense that if the young scholar’s magic reinforced a love spell, his ancestor might be connected to love in some way. Acheron had used a male pronoun, which ruled out Aphrodite, so her son, Eros, was the most logical candidate.

A water spout broke the surface and sprayed so hard that it nearly hit the roof of the cavern. “You are indeed his descendant. But do you know from whence he and his mother both derive their power?”

It was a good thing I had paid attention to the old creation stories. “Do you mean the original Eros, love incarnate?”

“Exactly. One of the primal powers, the spark that set in motion the creation of most of the universe, whose first king he became. Do you know what this means?”

“No,” said Menippus, wondering about Acheron’s sanity. The river god seemed to be losing the thread of the conversation.

“It means that you might be able to bend Empusa to your will. Primal Eros could do that for you. And though he is everywhere, filling the universe with his presence, he is also in the darkness of the Underworld, where he lives in the Cave of Night, his daughter and successor.”

Menippus didn’t want to look the proverbial gift horse in the mouth, but the story seemed too good to be true. “Will he really help me?”

“He might—but not if you approach him as the spirit of a mortal. You could never even reach him in your current form. You must destroy all that is left of your mortality and become a god.”

“How would I do such a thing?”

If the judges might have condemned him for blasphemy before, they certainly would now.

“I have been here for untold ages, but I have sometimes heard stories,” said Acheron. “Occasionally, the dead mutter to themselves as they wait for Charon. Heracles burned away his mortality lying on his funeral pyre and became a god. It is possible that your mortality may be destroyed in my waters, leaving only a god behind.”

“Can that really be?” Menippus asked. “Even if the Heracles story is true, he was half god, not some tiny fraction as I am. And it was his physical body that burned, not his soul. As far back as Socrates, philosophers have argued for the immortality of the human soul.

Acheron rose partway out of the water then. As in the stories, he had horns like a bull. But unlike the way river gods were described, his skin was pale, no doubt from being cut off from sunlight. His expression was hard as stone, almost as if he had gazed upon Medusa herself. Only his eyes confirmed that he still lived. They were black orbs, but where pupils should have been blazed tiny, dark flames. Were they some dying remnant of his father’s light? Or were they a glimpse at the desire for revenge against the gods that burned within him?

“From what I know, the soul is immortal, but not unchangeable,” said Acheron. Unfiltered by the water, his voice sounded as deep as his hatred of the gods was vast. “Aside from Heracles, humans have become gods before, though such an apotheosis is rare. Surely, when such a thing happens, their souls must cease being human souls and become godlike.”

Menippus longed to believe Acheron, for the river god offered hope. But as Menippus gazed into the dark flames of the river god’s eyes, he wondered why such a bitter being would help a forlorn lover.

“But do not such transformations typically involve a blessing from Zeus?” Menippus asked. “Or from some god, at least?”

Acheron’s dark flames burned more brightly. But his face remained inert, and his voice didn’t betray any anger at Menippus. “Glaucus, the fisherman, was transformed into a god by eating a magic herb. It was an accident, as far as I know. But you have before you a god who will bless such a transformation I may not be Zeus, but I am ancient and powerful. Do you doubt me?”

Acheron was ancient and powerful—but he was also a prisoner in the Underworld. How much real power would Zeus have allowed him to retain? Was it not more likely that behind those flaming eyes lurked madness?

But who was Menippus to judge? Almost everyone would see his love for Empusa as madness, yet he would deny that accusation from now until the universe itself ended. Should he not give Acheron the benefit of the doubt?

“I lack the gift of prophecy,” said Acheron. “In truth, I cannot be sure what will happen. At worst, perhaps we will discover that the human soul is mortal after all, and you will be destroyed. Perhaps you will just be damaged so badly that you will long for complete destruction. But at best, you will become a god and have the possibility of winning your love. If your desire is as strong as you say, you will take the chance. Or are you too cowardly?

Menippus stiffened at the taunt. He had already risked his life and lost. He might be a fool. He might even be a madman. But a coward? Never!

Despite his resolve, he still hesitated, though. The river god’s unmoving face was impossible to read. Was he trying to help a fellow sufferer or to destroy an annoying mortal who had awakened him to face more misery? There was no way to be sure. But even destruction would be preferable to eternal separation from Empusa.

Or so Menippus thought until he dived into the water. Part of him had hoped that he could not feel pain without a physical body. But that proved to be a vain hope. A water burned him like acid—a magical pain for a non-physical body. The sensation spread across every inch of his skin. No, not just his skin. The pain spread through his entire body as the acid had burned through him, ravaging every part of him all at once.

Even worse than what felt like physical pain was the despair that filled his heart to bursting. The same water that burned him with pain also chilled him with sorrow. He would fail, and he would lose Empusa forever. He tried to turn back, but he lacked the willpower to make even such a simple move.

He screamed so loudly that the other ghosts were frightened, so loudly that Charon must have taken notice, though he didn’t react in any way Menippus, trapped in his own personal hell, could perceive.

But something did pierce through the veil of torment. Menippus was surprised to feel the river god’s arms around him. The god seemed to have little control over the river in which he lived, but it was clear he still had power of some sort. The solidity of earth radiated from those arms, as did the warmth of the sun, even though Acheron had felt neither since the earth was young.

His presence—and only his presence—saved whatever sanity Menippus had left. Perhaps it even prevented his destruction.

As Acheron continued to grip him, the nature of the power he sent to Menippus changed. Earth and sunlight became fire, as if the dark flames in Acheron’s eyes now burned within the young scholar. As they burned, Menippus felt himself becoming more like Acheron. The river god’s immunity to the water of his own river spread through Menippus. As it did so, he felt his pain and despair fading as a nightmare fades when a sleeper wakes.

Menippus no longer felt pain. All he felt was the sensation of Acheron laying him on the opposite bank of the river.

The young scholar had crossed. It had taken a lot of help, but he had done it. In his mind, the nightmare had already transformed itself into a dream. He also felt much lighter than before.

Acheron eyed him speculatively. “There is not much left—but there is something. In time, a body such as we gods have will manifest.”

Menippus looked down and saw that his human form was gone. Instead, he appeared to be only a mist in a vaguely human shape. Whatever he had inherited from Eros was really all that remained of him.

Well, that and his memories of Empusa. Perhaps now, with his humanity gone, he would be more attractive to her.

Menippus looked over at Acheron, and the young scholar felt as if he were looking at a brother. He knew that that the pain and sorrow the river water had struck him with were Acheron’s own feelings, and that the river god was not so much immune to them as used to them. Having shared those feelings, the young scholar and the river god were now kin and always would be.

“What must I do now?”

“Now you must wait,” replied Acheron. “Wait and become stronger. Wait and plan your revenge upon the gods, who will certainly not see you coming.”

Menippus had portrayed himself as a victim of the gods just to get help from Acheron. But as he listened to the river god’s words, he realized that he did want revenge upon the gods, if only for creating such an unfeeling world in which true love could be defeated.

He would wait, just as Acheron said. He would grow strong. His own eyes would flame.

And when the time came, he would make Olympus tremble.

Interesting expansion of the gods’ stories and motives from the simple myths I read as a kid…and the illustrations are wow!

I can't wait to have you read the opening chapters of The Sibyliad. So many similarities.